Clyde Kennard – Forgotten Hero of the Civil Rights Movement

by Samuel Bruton, Ph.D.

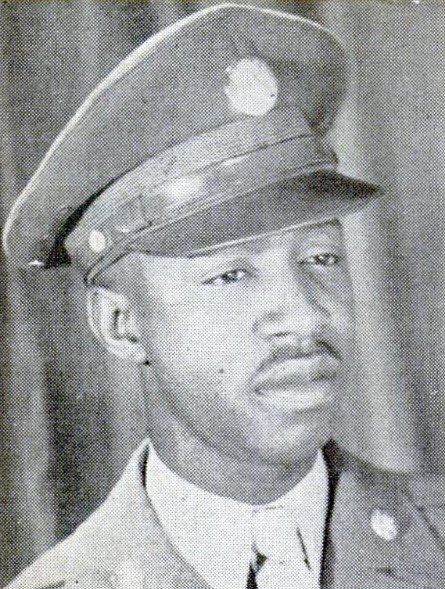

Clyde Kennard in army uniform

Newspaper article detailing Kennard’s denial of admission and imprisonment. Read text version of article.

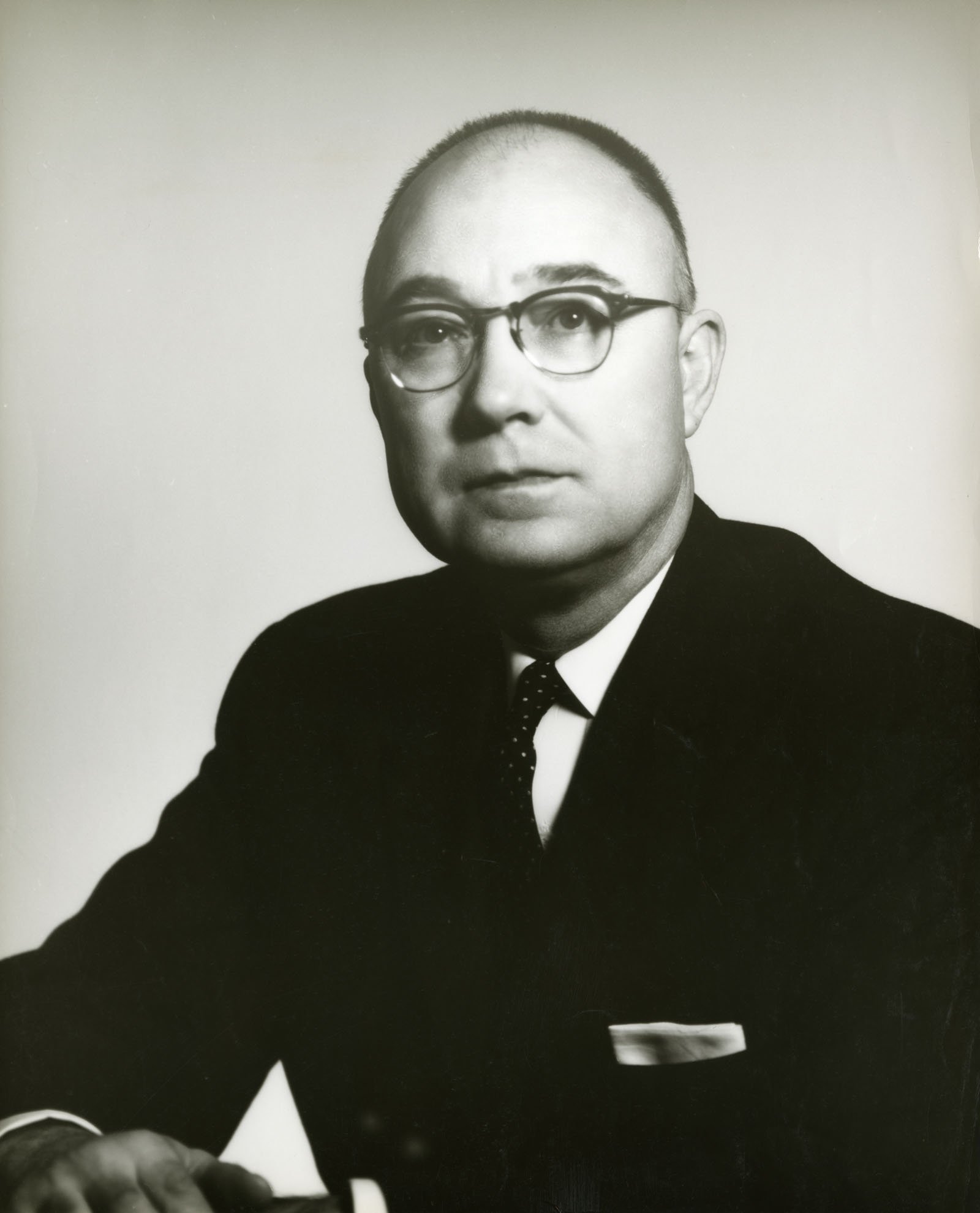

William D. McCain, president of USM when Kennard attempted to enroll

Clyde Kennard (1927 – 1963) was a true hero of the Civil Rights movement, although he remains little known outside of Hattiesburg. His story is both an inspiring example of moral integrity and personal commitment for the cause of racial justice and a tragic tale of unconscionable acts white Mississippians performed to preserve their Southern “way of life.”

Born in 1927 in Hattiesburg, Kennard moved to Chicago when he was twelve to live with his older sister and attend school. He joined the Army at age eighteen and served for seven years as a paratrooper in Germany and Korea before being honorably discharged. Some of the money from his military service he used for a down payment on a twenty-acre farm for his mother and stepfather near Eatonville, Mississippi, about eight miles from Hattiesburg, and he began to pursue a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Chicago. However, in 1955 Kennard’s stepfather died, and he moved home to help his mother run the family farm, one year shy of finishing his studies.

Soon after returning home, Kennard attempted to enroll at the University of Southern Mississippi–then called Mississippi Southern College–to complete his degree. His first application was denied in 1955 because he lacked the required five alumni references from his home county. Mississippi Southern had always been all-white, and the reference requirement ensured that it remained that way. McCain later admitted privately to the Sovereignty Commission that Kennard’s grades were above average and, except for the alumni references, Kennard met all the admissions requirements.

Kennard resumed his enrollment efforts in the fall of 1958, requesting several blank applications from admissions director Aubrey Lucas to give to “other Negroes in the Eatonville community…who are possibly interested in making application for entrance to Mississippi Southern.” Concerned about this development, the secretive state-funded Mississippi State Sovereignty began a covert investigation into Kennard, led by former FBI agent Zack Van Landingham. After the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, white leaders in the state had been fearful of federal involvement in the state’s affairs, and in response they formed the state’s Sovereignty Commission to combat racial desegregation. Kennard’s involvement with the local NAACP had put him on the Sovereignty Commission’s radar screen, as did the perceived militancy of blacks in the Eatonville area.

On December 6, 1958, Kennard published a letter to the editor in the Hattiesburg American arguing that blacks should be able to attend Mississippi Southern, and he announced his intention to enroll in early January. Meanwhile, the Sovereignty Commission investigation was having difficulty finding the kind of disparaging information it sought to discredit Kennard. Van Landingham hatched a plan to dissuade Kennard from enrolling by enlisting the assistance of several prominent black educators, including N.R. Burger, A.B.S. Todd, and J.H. White. After meeting with them, however, Kennard refused to change his mind. Governor Coleman met with Kennard in his office in early January, arguing “it was not the appropriate time” for Kennard to attend Mississippi Southern and that the situation “was going to take time to change.” In response, Kennard agreed to withdraw his application.

His change of heart did not last long. On August 26, 1959, Kennard told McCain of his intention to apply for the fall semester. Whites in the area tried to exert economic pressure on him, and on September 7, McCain met with Kennard for almost an hour trying to dissuade him, but Kennard was resolute. The following day, Kennard wrote a long application letter to Lucas, rebutting traditional arguments against integration and threatening to take his case to federal courts. Black educators met again with Kennard, but to no avail. On September 14, Van Landingham reported that Kennard’s mind could not be changed “no difference how much pressure was put to bear on him.”

Report to the Sovereignty Commission on Kennard’s intent to enroll. Read text version of report.

On September 15, acting under Coleman’s direction, McCain duly informed Kennard that his application was rejected because his papers were “not in order.” To keep him away from the press, Kennard was taken out of the President’s office by a side entrance. Upon returning to his car, Kennard was arrested by two Forrest County police constables for “driving at an excessive speed” and “illegal possession of whiskey.” Apparently, the constables were acting on their own initiative; even Van Landingham described the arrest as a “frame-up.” Two weeks later, Kennard was found guilty of both charges. Undeterred, Kennard published another letter in the Hattiesburg American on September 25, attempting to reassure anxious whites. Eloquently as always, Kennard claimed “What we want is to be respected as men and women, given an opportunity to compete with you in the great and interesting race of life. We want your friends to be our friends; we want your enemies to be our enemies; we want your hoped and ambitions to be our hopes and ambitions, and your joys and sorrows to be our joys and sorrows.” This was followed by a third letter to the paper in February 1960.

Kennard’s plight took a dramatic turn for the worse in September 1960 when the Forrest County Cooperative, where Kennard purchased feed for his chickens, was burglarized. Johnny Lee Roberts, the burglar and an employee of the Co-op, claimed Kennard had planned the theft. Kennard was arrested on felony accessory to burglary charges and convicted by an all-white jury in November 1960 and sentenced to a seven-year prison sentence at Parchman Penitentiary. Roberts’ incoherent and confused testimony on the witness stand was the sole evidence against him. In return for his testimony, Roberts received only probation.

About a year after arriving at Parchman, Kennard began to complain of intense abdominal pain which was eventually diagnosed as stomach cancer. Prominent black leaders, such as Medgar Evers, worked for Kennard’s release, but these efforts came to naught until a Jet magazine exposé shocked northern whites. To avoid further bad publicity, Governor Barnett grudgingly released Kennard, but by then it was too late. Kennard died of cancer on July 4, 1963.

Some small measures of justice for Kennard were attained only decades later. In 1993, the University of Southern Mississippi’s student services building was renamed Kennard-Washington Hall to honor Clyde and Walter Washington, the first black individual to receive a doctoral degree from Southern Miss. In late 2005, Johnny Lee Roberts recanted his testimony against Kennard, leading Forrest County judge Robert Helfrich to overturn Kennard’s conviction. In 2018, the Clyde Kennard Mississippi Freedom Trail marker was unveiled in front of Kennard-Washington Hall.

Sources:

Dittmer, John. Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi. Chicago: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1994.

Katagiri, Yasuhiro. The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission: Civil Rights and States’ Rights. Jackson, MS: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2001.

Minchin, Timothy J. and John A. Salmond, “‘The Saddest Story of the Whole Movement’: The Clyde Kennard Case and the Search for Racial Reconciliation in Mississippi, 1955-2007,” The Journal of Mississippi History LXXX1 (no. 3) (Fall 2009): 191–234.

VanLandingham, Zack J., “Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission: Report by Zack J. VanLandingham,” Dec. 17, 1958, 4, in RG 27, no. 132, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Kennard while in the hospital

Newspaper article on Kennard’s posthumous reputation. Read text version of article.